What is a country to do when as much as 78% of its flights are operated by one of two airlines? Canada’s Competition Bureau believes more airlines operating within the country will address the Air Canada/WestJet market domination. And it believes foreign investment is key to getting those airlines off the ground.

Sheltering companies from competition does not create national champions. As renowned economist Michael Porter famously stated, “unless a firm is forced to compete at home, it will usually lose its competitiveness abroad.” If a company faces little competition at home, it is ill-prepared to compete elsewhere.

– Canada’s Competition Board Report

To that end the government agency is proposing to reduce restrictions on foreign ownership of airlines, including allowing 100% foreign ownership if an airline operates only domestic flights in Canada. The group also recommends that Canada work with foreign countries to allow cabotage – foreign airlines operating flights wholly within Canada – to increase competition.

Fully Foreign Owned. Or Not.

Recognizing that foreign ownership rules can play a role in international air service agreements – the treaties that define which airlines can operate where on international routes – the Competition Bureau does not believe that transitioning to a 100% foreign ownership approach today is viable for all services in Canada. But for airlines operating only on domestic flights those treaties do not apply. Thus the idea that a wholly domestic airline be permitted to operate even if foreign-owned.

For any airline operating internationally a 49% limit is recommended to comply with those treaties. It also suggests that negotiations be opened to increase that level over time.

The agency also recognizes that a foreign airline (or foreign ownership) would likely focus on larger markets first, chasing the most profitable traffic. This could cause airlines to trim services in smaller markets, as the connecting feed no longer delivers the right profit margins.

Aviation is a network industry. So changes to airlines’ profits on a single route can have cascading effects across the system. If earnings decline on major routes, airlines may no longer serve regional communities. This again could reduce Canada’s connectivity.

In the present business model, profitable main routes may subsidize essential regional service. They may no longer be able to do so if foreign competition threatens those major routes’ profits. Once more, connections between regions could be threatened.

To address this concern, however, the Competition Bureau suggests simply subsidizing the less profitable routes to ensure continued service.

No airline – Canadian or foreign – has to fly routes that lose money. If rules are blocking foreign competition to protect regional service, policymakers should make this trade-off known and look at it more closely. Instead of blocking competition, regional routes could be supported directly. The government could hold auctions where airlines bid for subsidies. This would find the most cost-effective way to keep these routes running while allowing competition that benefits all passengers.

This approach would, in effect, mean the Canadian federal government would subsidize its domestic carriers to offset their reduced profits in the face of foreign competition. That seems a long way around to having people who aren’t flying offsetting the fares for those who are, while also funneling a good chunk of travel cash out of the country.

While perhaps this results in lower fares in some markets for the air travelers of Canada, it is a questionable use of taxpayer funds. And the Bureau knows this, mentioning earlier in the report, “[G]overnment subsidies do not lower costs—they just change who pays them. Subsidies may help, but governments have to weigh the economic and social benefits of greater connectivity against the costs of subsidies.”

Still, this approach is part of the recommended plan. Foreign operations in Canada “alone will not solve all competition issues” But the group believes “it represents a critical step forward.”

But Will It Work?

In making the recommendation the Bureau cites several countries that similarly shifted their policies. Chile, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Singapore, and Hong Kong all allow the ownership test by principal place of operation rather than where the money comes from. Australia and New Zealand have similar limits to what is recommended (100%/49%). And the EU single aviation market allows foreign ownership and cabotage.

While it cites these examples as supporting its position, it also admits there have been failures.

Tigerair, Bonza, and Rex all failed in the Australia/New Zealand market. Jetstar Asia just announced a rapid winddown of operations from its Singapore base.

Europe has seen a steady beat of consolidation over the past decade. This leads to increasing challenges for smaller airlines – even well-established ones – to compete without strategic partnerships. SAS and TAP Air Portugal are the two latest to reflect those challenges. Perhaps lower fares in the Italian domestic market – where Ryanair runs significant operations – is the counterpoint of success. But there are few such stories.

Financial success has proven fleeting for airlines of Latin America, with multiple bankruptcy filings in recent years (also COVID-19, of course).

But if the fares go down for passengers do the commercial failures matter?

Transparency Benefits Consumers, but Not Enough to be Required

The Competition Bureau report also recognizes that consumers face a more complex landscape than ever in comparing fares, owing to unbundling and the variance in ancillary fees charged.

Consumers are able to make better choices when they can find, understand, and compare products, services, and prices. They can better decide on the options that most meet their needs. This informed decision-making benefits consumers directly, and it makes the market more competitive. This in turn can lead to lower prices and better service quality…

The complexity of airlines’ fare categories and optional extras can make it difficult to properly compare flights. This challenge is most striking for infrequent flyers….

Overall, this booking process can be complex for customers to navigate. Even tech-savvy consumers can be affected, but it’s worse for those with less time and resources.

And, ultimately, the Bureau chose to not recommend changes on this front. Instead, it recommends the current approach as it “allows airlines to evolve different fare structures based on real consumer behaviour and preferences. This process is more likely to discover workable solutions than regulating standard fare categories.”

An Internal Failure From the Bureau?

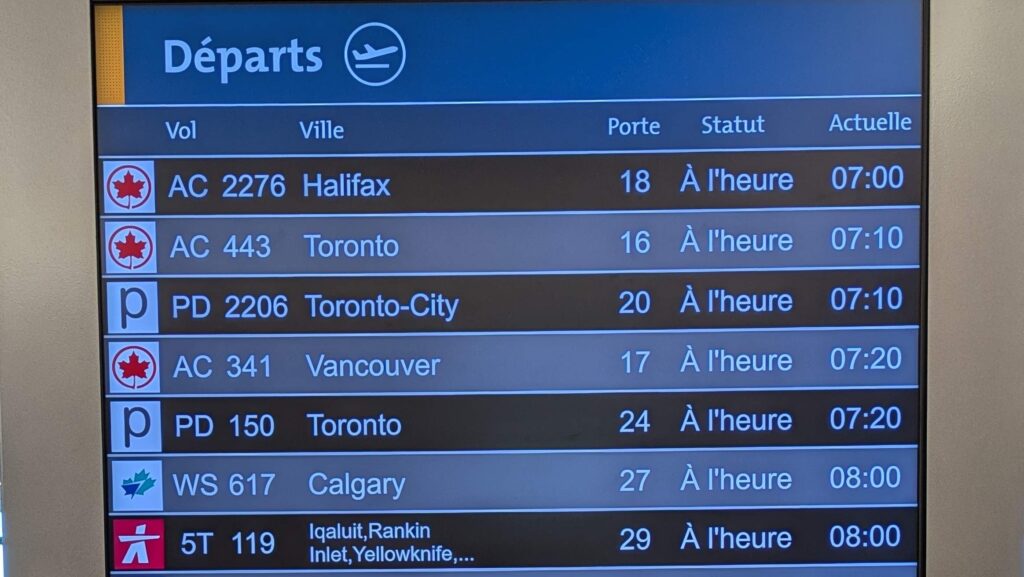

Interestingly, the Competition Bureau also notes that it allowed for predatory pricing to kill off an upstart airline attempting to launch Ottawa-Iqaluit service in 2016. This, of course, seems counter to all its talk about ways to increase competition. At the time, however, it determined that the incumbents’ lower fares – specifically adjusted when the new carrier showed up and removed after – were “not consistently pricing below average avoidable costs,” so they remained legal. Even if that meant preventing another airline from competing.

Nowhere in its recommendations does it suggest addressing that incongruity.

The full report from the Competition Bureau is available here.

A favor to ask while you're here...

Did you enjoy the content? Or learn something useful? Or generally just think this is the type of story you'd like to see more of? Consider supporting the site through a donation (any amount helps). It helps keep me independent and avoiding the credit card schlock.

Leave a Reply